Eglantyne Jebb, 1876-1928, Founder of Save the Children and champion of children’s rights

Table of Contents

Eglantyne Jebb, an unlikely children’s champion?

‘To succeed in life, you must give life’ Eglantyne Jebb once wrote. But she herself did not give life in the traditional way expected of a well-to-do Edwardian lady – by marrying and having a brood of children. In fact Eglantyne confessed she was not fond of children, once calling them ‘the little wretches’, and looking back she claimed that ‘the dreadful idea of closer acquaintance never entered my mind’. Instead she chose to ‘give life’ from a strategic distance by setting up the Save the Children Fund at the end of the First World War. She went on to write the pioneering statement of children’s human rights that has since evolved into the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, the most universally accepted human rights instrument in history.

The formation of Save the Children

Eglantyne Jebb photographed at her desk

In 1919 Eglantyne was arrested in Trafalgar Square for handing out leaflets featuring photographs of starving Austrian children that had not been cleared by the government censors. A few of these leaflets still exist, slightly crumpled, in the Save the Children archives, and on the top of one the word ‘suppressed!’ is pencilled in Eglantyne’s unmistakable scratchy handwriting. The exclamation mark expresses her outrage at Lloyd George’s Liberal government’s policy to continue the economic blockade to Europe after the end of the war as a means of pushing through war reparations, whatever the human cost.

The government hoped that arresting Eglantyne might shut up this passionate but irritating woman who had been lobbying them for some time along with her influential friends Lord Parmoor, John Maynard Keynes and others. They were wrong. Eglantyne represented herself in court, focusing on the moral case. Although found guilty she was only fined £5, which, she wrote to her mother, ‘is equivalent to victory’. The crown prosecutor – the only man in this tale with a name to rival Eglantyne’s – Sir Archibald Bodkin, then publically pressed £5 into Eglantyne’s hands. This became the first donation put towards a new fund to bring relief to the starving children of Austria and Germany – the Save the Children Fund.

By morning the story was all over the papers. But Eglantyne was not satisfied – press columns alone did not feed children. To capitalise on the publicity she and her younger sister, Dorothy Buxton, called a public meeting at the largest venue they could hire – the Royal Albert Hall. The sisters were nervous that no one would come; charity was believed to start at home, and certainly not with the children of recent enemies. In the event the Albert Hall did not have enough seats for everyone who arrived. Unfortunately for Eglantyne however, half of the crowd had come with rotten fruit to throw at the traitor sisters who wanted to give succour to the enemy. A nervous speaker at the best of times, Eglantyne was now terrified. She began quietly, but her voice rose with her passion until at last she called out, ‘Surely it is impossible for us, as normal human beings, to watch children starve to death without making an effort to save them’. A collection was taken up as the hall erupted with applause, and £10,000 was raised and delivered in aid to Vienna within just ten days.

What if not maternal impulse?

Later that year Eglantyne wrote with typical dry humour to her close friend Margaret Keynes, the younger sister of the economist, ‘I suppose it is a judgement on me for not caring about children that I am made to talk, all day long, about the universal love of humanity towards them’. She was driven not by a sentimental concern for individual children, but by a passionate, undiscriminating, humanitarianism that many had lost sight of at the end of the war. She also had other motives. Early research she had commissioned showed that while adults can, to some extent, recover from a period of starvation, children may never be able to make up the lost ground both physiologically and psychologically, so they really should be the first to receive relief. Furthermore children were the next generation, responsible for delivering what Eglantyne hoped would be a more just and peaceful international society. But Eglantyne was also a savvy fundraiser who recognised the emotive appeal of children. One of the first people to employ the power of celebrity endorsements for charitable purpose, she was particularly fond of quoting a line by George Bernard Shaw: ‘I have no enemies under the age of seven’.

Globalisation

Brought up in the Church of England, Eglantyne now wrote to the Archbishop of Canterbury, asking him to donate collections on one day close to Christmas. Wishing to avoid involvement with such an apparently political organisation, the Archbishop declined. Eglantyne simply wrote to the Pope, who invited her for an interview. The Pope’s meeting with Eglantyne is recorded in a charming letter she wrote home to amuse her mother. The Pope was running behind schedule, but finally an emissary arrived, shouting in Italian, in which Eglantyne could only make out the word ‘come’, before he set off at a run. Eglantyne describes him with his purple robes billowing out behind him like a dressing gown, and then bounding down a corridor ‘like a purple bouncing ball’. Finally they arrived in a grand hall at the end of which stood a figure ‘standing, lonely as a ghost’ and, remembering that Popes always wear white, she dropped to her knees. The Pope kept her for two hours, scribbling ‘in a dirty little notebook’, and then contributed £25,000 of his personal money before promising that Catholic Churches all round the world would contribute to the Fund. The Church of England and several other faith groups now came together for an unprecedented international inter-faith collection in support of the Fund on Holy Innocents Day. Save the Children was placed firmly on the international map with sister organisations quickly appearing all over the world.

Recognising children’s rights

Eglantyne Jebb - a self portrait

Eglantyne was still not satisfied – she was like that. In 1922 a story has it that she climbed to the top of Mount Salève, outside Geneva, to clear her mind. Settling down on the crisp turf, her hair blowing in the breeze, she looked down over the international city and drafted the pioneering statement of children’s human rights that has since evolved into the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child - forever changing the way the world regards and treats its children.

Eglantyne died just six years later. She was only 52. By then she had won over most of the aristocracy, and the trade unions, the Pope, and the Bolshevik government, the wife of the Prime Minister who had arranged the economic blockade, and the fledgling League of Nations in Geneva. Although children’s human rights are yet to be fully realised, Eglantyne’s achievement in putting them on the world agenda is powerful testament to the power of the humanitarian spirit. Eglantyne found individual children noisy and tiring, but she recognised that children are unique both in their potential to suffer, and their potential to give - as the future generation. It is at our peril that we fail them.

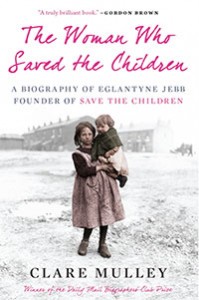

Clare Mulley’s book, The Woman Who Saved the Children: A Biography of Eglantyne Jebb, Founder of Save the Children is available in all good bookshops and on Amazon. It won the Daily Mail Biographers’ Club prize. Prime Minister Gordon Brown called it ‘a truly brilliant book’, and Paul O’Grady wrote ‘pick up this book and be inspired’. All author royalties are being donated to Save the Children. www.claremulley.com

Clare Mulley’s book, The Woman Who Saved the Children: A Biography of Eglantyne Jebb, Founder of Save the Children is available in all good bookshops and on Amazon. It won the Daily Mail Biographers’ Club prize. Prime Minister Gordon Brown called it ‘a truly brilliant book’, and Paul O’Grady wrote ‘pick up this book and be inspired’. All author royalties are being donated to Save the Children. www.claremulley.com

[…] Figure 1 Eglantyne Jebb (First writer of the DRC) Ignorant or […]

I was disappointed with Clare Mulley’s book. I wanted to learn more about Eglantyne Jebb. I expected the book to be a respectful read. Why did the author put herself at the centre of her own book by describing her own personal fart when she visited Eglantyne’s grave? Why does she think any reader would be interested in her problems with wind? That tells more about the author than the subject and shows disrespect for readers no matter how much praise the book has had. I did not pass it on to my daughters, I got rid of it.

I also lost interest in Save the Children and have not been back in one of their shops since. Children need more than food clothes and shelter.

touched by her devotion. let somebody out there be encouraged by our decision to affect the lives of the younger generation.

[…] on the verge of collapse and children in these countries were starving. Moved by their suffering, Eglantyne Jebb was arrested for handing out leaflets about their plight in Trafalgar Square. Jebb was from a […]