Railwaywomen: from backstage heroine to train driver

Table of Contents

Overview

Railways are imbued with maleness to their very core. Everyone connected with the creation and operation of railways was male: business men and financiers, architects and engineers, navvies and bricklayers, managers and operating staff. The masculinity of railways was reinforced by military uniforms, a strict hierarchy of rank and severe disciplinary procedures, all of which were modelled on those of the armed forces.

Before 1915 the exclusion of women from almost all employment on the railways did not need to be justified. It ‘went without saying’ that railway work was ‘man’s work’. Women were hired by railway companies only in two circumstances: either to perform work that only women could (or would) do, or to replace men in jobs where they could be paid less. (Level crossing gatekeeping had both elements; often only a railwayman’s wife could obtain a position because it was intertwined with his job. If widowed, she was retained because she was cheap and needed no training.) For reasons of propriety only women could work as ladies’ room attendants and as ships’ stewardesses to attend to lady passengers, while office-cleaning, laundering and sewing were regarded as women’s work. To save money women were utilised wherever possible as, clerks, French polishers, hostel attendants and canteen staff, on less pay than the lowest-paid men.

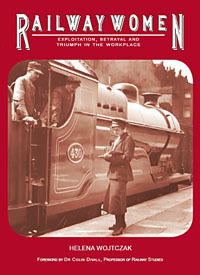

Stationmistress and her porters, 1917.

Irlams O Th’ Height, Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway.

Picture taken from author’s website www.hastingspress.co.uk

The two World Wars opened up opportunities for women. They took on all the jobs, including dangerous ones, previously done by men, at a time when the railways were regularly a target for attack. However, once men returned, women were again sidelined and those who remained found the working environment hostile.

The Railways Act 1993 privatised the industry and British Rail was disintegrated into a hundred separate parts, each one sold or franchised separately. The negative effects of privatisation for women have already started to show. Most carriage cleaning, for example, is now contracted out to cleaning companies, whose employees are not railway workers and so do not receive the many benefits that their predecessors enjoyed, such as free rail travel, entry to the railway pension scheme and trade union representation. Nevertheless, nowadays railwaywomen have equal pay and equal opportunities. There is probably no job on Britain’s railways that is not done by at least one woman; several managing directors of railway operating companies are women. And, at last, women are train-drivers—something that would shock and alarm the railway men of the past.

Women’s work on the railways

Women began to work on the railways around the 1830s. At that time conditions for Victorian railwaymen were harsh, but railwaywomen were treated even more shoddily. They were earmarked for the lowest-status jobs with almost no hope of advancement, and at half to two-thirds the wages of men. Women’s exclusion from the unions meant that railwaymen’s status might be improved while their female colleagues were left behind as they became the weakest link in the chain of the labour movement. However, the admission of women into railway offices from the 1870s gave some of them access, through membership of the Railway Clerks’ Association (RCA), to the wider labour and trades union movements.

Railwaywomen gradually increased in number between 1830 and 1914. Some blue-collar workers amassed long service, in some cases as much as forty and even fifty years, which belied the oft-stated belief that every woman worker was short term. Office workers were dismissed upon marriage, but many spinsters gave long service.

During the First World War almost one-third of male railway workers joined the Forces, leaving the industry in a terrible crisis. Jobs that had always been rigidly closed to women were suddenly opened to them and there was a stampede for jobs. Railwaymen did not disguise their opposition to women. Their union leaders grudgingly accepted that women were needed to keep the railways running but insisted they be ousted when war ended. The proportion of female staff increased from 2% to 16% in four years. By 1918 there were almost 66,000 female railway employees, of which about half were in uniformed, manual work never before performed by women. 10,000 became ticket collectors, luggage porters, parcels porters and goods porters, handling heavy goods such as sacks of coal or flour, animals and milk churns. They worked on stations, sometimes being the only woman amongst a group of men. At other locations the stationmaster was the only man among a staff of twelve.

Women also became pointswomen in marshalling yards, previously considered too dangerous an environment for women to work in; for the first time, female carriage cleaners were allowed to work on the track. Women worked as goods carters, having charge of a horse and cart to deliver parcels and luggage by road. To the disgust of the train drivers’ union Aslef, who refused to recruit them, women were engaged as engine cleaners. Globers cleaned and filled the oil lamps in carriages; they climbed up a ladder welded to the rear of a carriage then walked along the roofs, jumping from carriage to carriage. In the carriage and wagon department women carried out a wide range of maintenance tasks. They climbed beneath carriages and wagons, tightening the bolts on axleboxes, replacing timber running boards and setting up the brakes. Women did a wide variety of jobs in the workshops, for example operating capstan lathes and high-level cranes that were used to lift freight or even steam engines.

Union opposition

While railway managers were impressed by women’s competence, the same cannot be said of the unions. Throughout both wars, Aslef never wavered from the belief that women should not clean engines. The attitude of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR) was more ambivalent. Before the war things were simple: women were kept out of men’s jobs and excluded from the union. In 1915 they became union members and entitled to the same privileges as men. When forced to choose, however, loyalty to the male sex over-rode loyalty to a sister union member every time.

In London and Scotland women were employed as guards (the person who rides on the train and is in charge of passengers, safety and timekeeping), which made railwaymen uneasy. When a few were recruited as signalwomen, railwaymen responded by trying to prevent them from being trained and to oust those who had already qualified. The men threatened to strike, which during wartime was a decision not taken lightly, and insisted that members of the ‘weaker sex’ lacked the ‘clear-sightedness’ and ‘level-headedness’ which ‘nature’ had bestowed solely upon men. But women guards and signallers turned out to be perfectly competent. It was said that women would ‘go to pieces’ in emergencies, but when put to the test they proved the assertion untrue.

The men feared that women would undercut men’s rates and be a ‘scab’ army in the event of a strike, yet women campaigned long and loud, and in 1918 some even went on strike for equal pay. Railway bosses stated that all women needed less money to live upon: they were either spinsters or had a husband’s income. This rough-and-ready ‘means-testing’ was not applied to male staff.

When the war ended there were nearly 66,000 female railway employees, working in hundreds of capacities. There was no practical reason why women should not have stayed on (heavy war casualties left 20,000 railway vacancies). But the 35,000 women filling male jobs in November 1918 had dwindled to fewer than 200 by 1923. By the mid-1920s women were again relegated to the worst-paid, lowest-status work. However, tension and resentment grew as women gained from men over 7,000 clerical positions, nearly 700 jobs as carriage cleaners and about 100 crossing keepers’ posts—in which occupation women outnumbered men for the first time by 1926. Women also gained more than 200 jobs in the marine division.

The Second World War

Engine cleaners at Newcastle, Heaton, LNER, 1942.

Picture taken from author’s website www.hastingspress.co.uk

At the outbreak of the Second World War over half a million men and 25,000 women worked on the railways. Of the women, about 11,000 were in offices, 7,000 in hotels and catering and 7,000 in female manual work (i.e. cleaning). Thousands of railwaymen joined the Forces in 1939 and women were—once again (and rather miraculously)—deemed to be capable of men’s work. In addition to filling all the posts women had filled in the First World War, their range of tasks broadened. This time they were employed on track work, as electricians’ and engineers’ assistants, jointing cables, and repairing and oiling semaphore signals and associated wiring, oiling points, packing ballast and tightening the bolts which hold the rails onto the sleepers. They became fog signallers, standing alone at an isolated signal-post for hours on end in freezing fog, laying detonators on the line. They were pilotwomen, travelling on engines along single lines; they became porter-shunters, who climbed down on the track between engines and carriages and uncoupled and coupled them.

Despite bitter opposition from men, many more were employed as guards; for the first time, they were put in charge of trains along the south coast, the midlands and London which, while all railways were a prime military target, suffered from particularly heavy bombing. Many more became signalwomen, and they were permitted to move up a rank or two and control the more complicated signalboxes, previously thought beyond their mental and physical capabilities. Women’s tasks in the workshops were also greatly expanded. They operated power lathes and drop-stamp hammers, and were trained as electricians. They climbed inside the workings of escalators to repair and maintain them. From 1941 women were conscripted and could be made to perform railway work.

After the war, most women were forced to leave any uniformed job to make way for a man. A handful managed to keep their jobs, most usually on a rural station or isolated signalbox that no man applied to work at. Some managers were apt to take a laissez-faire attitude to an individual woman, perhaps a war widow with dependents, who was obviously competent at her job, but union officials sometimes complained until the woman was dismissed and replaced by a man (even one with no railway experience).

The clock turns back for women

Between 1945 and 1975 there was, in theory, nothing to stop a woman from joining the railways as a porter, signaller, engineer or technician although this was not common knowledge. As far as Labour Exchanges and recruitment posters were concerned, these were male-only occupations. Attempts by British Rail in the 1960s and early 1970s to employ women as guards and signallers (because of desperate staff shortages that threatened its ability to deliver the scheduled services) provoked opposition from railwaymen that was so fierce that BR dropped the idea and never resurrected it.

By the 1970s railwaymen had effectively turned the clock back fifty years, for railwaywomen had returned to their 1920s position of being confined to the ‘three Cs’—cleaning, catering or clerical work. But even within those areas they could not get on. Promotion within cleaning and catering was hindered because women were not allowed to supervise or manage men. Women office workers were stalled by their male colleagues, their union and their managers, who condemned the employment of wives, would not let women work at night and publicly ridiculed the notion of female station-masters or yard-masters.

Government careers’ booklets always referred to railway staff as male and the NUR also played its part. When its newspaper ran a series of photographs depicting a wide range of railway workers, the only woman included was Mrs Hutchinson, who served tea in the station buffet at York. Within the railways, women were omitted from rules’ books and other publications, and the word ‘staff’ was synonymous with ‘man’. For example, one booklet explained that the Staff Association was open to ‘all grades of the staff, and their wives’, while another, for salaried staff, stated: ‘A married householder means a married male member of staff’. Anyone reading such material would naturally assume that women were not admitted to railway operating jobs. And yet some fell into railway work easily, perhaps hearing, through their railwayman father, husband or brother, of a porter’s vacancy in a quiet, rural station on some backwater branch line and applying for it. A few wartime signalwomen were sought out and invited to return during a 1950s staff shortage. It depended on the location, the availability of male labour and, most of all, the attitude of an individual local manager towards women.

Despite their absence from recruitment material there were so many isolated instances of women in male manual jobs that, nationally, they amounted to several hundreds in the 1950s, but with a total staff approaching half-a-million they were like needles in haystacks. Signalman Webster, a union activist, was bewildered to see an equal pay resolution on the agenda of the 1955 NUR Signalmen’s Conference, as he thought no women were employed in his job. (When he discovered that they were, incidentally, he immediately formed the opinion that they should not be.)

The Equal Pay Act 1970 gave employers five years’ notice before it had to be implemented. Railway workshopwomen received equal pay on 29th December 1975—just two days before the legal deadline! Equal pay was of no benefit to women in ‘women’s work’ who had no man to be equal with, but the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 meant women could enter any railway occupation on the same terms as men. From that year a few women, of which I was one, applied to be trained as guards, drivers, trackworkers, ticket collectors, supervisors, managers, engineers and train fitters.

Each woman in each job was isolated from similar women because they were all at different depots and stations across Great Britain, yet all faced similar obstacles, ridicule and opposition. The problems of staff toilets, uniforms and maternity were not addressed nationally; it was left up to individual women to fight identical battles in separate locations with varying degrees of support or opposition from their colleagues and union officials. Most suffered harassment from railwaymen on a daily basis, in the form of verbal abuse and obscene graffiti; while there were many cases of physical assault of a sexual nature. In 1978, when I was twenty, my manager asked why I wanted to be out ‘at all hours in all weathers’ as a guard when I could earn twice as much ‘just laying on your back on a nice, warm bed’ (i.e. by being a prostitute). Complaints to managers or to union representatives were routinely met with sentiments that amounted to ‘if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen’. Women who resigned were cited triumphantly by railwaymen as proof of women’s inherent weakness and their unsuitability for railway work and used to ridicule those women who remained.

The railway industry is one in which the role of women has been almost completely ignored by historians. Although over 170 years many hundreds of thousands of women have worked in hundreds of different jobs that encompassed everything from toilet cleaner to chief inspector of railways, books, articles and websites on railway workers routinely omit women. Such omission contributes to the invisibility of railwaywomen and serves to shroud their varied, fascinating and at times heroic history.

by Helena Wojtczak. Helena is an historian who has written a ground-breaking book on women on the railways. She runs the Hastings Press which publishes books on women’s history and other titles.

Further reading

Helena Wojtczak, Railwaywomen: Exploitation, Betrayal and Triumph in the Workplace. The Hastings Press (2005).![]()

Also visit Helen’s website: www.hastingspress.co.uk/railwaywomen/bookindex.html

Penny Summerfield, Women Workers in the Second World War. Routledge. 2012.![]()

Thanks for this article. I was looking for information on women who drove trains in WWll. I’m a member of the Guild of Railway Artists and wanted to paint a women driver and engine. Looks like I’ll have to choose one of the other jobs mentioned.

It’s absolutely fascinating. I didn’t realise the unions had been so anti women.