The King’s Smuggler

Jane Whorwood, Secret Agent to Charles I by John Fox (The History Press, 2010)

Reviewed by Amanda Capern

This intriguing book is an account of the life of Jane Whorwood. Whorwood’s main claim to fame is that she acted as a courier of money and information when Charles I was captive in Newcastle in 1647 and was part of a small royalist network that actively attempted to help him escape from Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight through1648.

This intriguing book is an account of the life of Jane Whorwood. Whorwood’s main claim to fame is that she acted as a courier of money and information when Charles I was captive in Newcastle in 1647 and was part of a small royalist network that actively attempted to help him escape from Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight through1648.

Whorwood was born Janna Ryder. She was the daughter of immigrants to London – her father, William Ryder, was a minor courtier and importer from Scotland, employed in the stables of James VI and I. Her mother, Elizabeth de Boussy, was a laundress for Queen Anne and originally from Antwerp. Whorwood was born in 1612 and when her father died in 1617 her mother married well, upwards, and she became the very marriageable step-daughter of James Maxwell, groom of the bedchamber to the then Prince Charles. Maxwell’s position enabled him to arrange a marriage for his step-daughter with Brome Whorwood who was heir to the estates of both his father and mother in West Bromwich and in Horton, Oxford. Maxwell offered a £2600 portion and amnesty for the Whorwood family from a hefty fine in Star Chamber.

These marriage negotiations are covered nicely in the book, but in other places there are what can only be called ‘fictional reconstructions’ where the dry facts of Whorwood’s life do not exist. This is particularly apparent for Whorwood’s early life: the Charing Cross would have been ‘Jane’s waking landmark in life’, the smell of ‘royal horse manure’ would have filled her baby nostrils,’ ‘manure liquefied with urine, wine, ale, and masked with herbs’ might have been given to her to alleviate the symptoms of the smallpox and ‘she may have had a language from her mother’. There are similar factual hiatuses at the end of the book. One can sympathise with the author – it is very frustrating trying to bring women to life in the past when the sources do not exist and this book does a creditable job of embedding its readers in the landscapes of Whorwood’s life.

Chapters on the period of the civil wars and their immediate aftermath are less problematic because some concrete sources do exist. They take the form of a small number of letters between Whorwood and Charles I (Egerton MS 1788, British Library), correspondence of the royalist circle to which Whorwood belonged and a small assortment of state papers in the National Archive. Fox has also fleshed out the facts of the narrative by using many sources in calendared form such as the Calendar of State Papers and reports of the Historical Manuscript Commission. He tells us that ‘the civil war period is fertile with drama’ and his book does not disappoint on this front.

After marriage in 1634, the drama which characterised Whorwood’s life provides the reader with a parody of the serious politics of the day. Her father-in-law dropped dead on the day of her wedding and her new husband, who was under 21, was fined for proceeding to consummate the marriage without his father’s consent. During the civil war her husband fled to Holland while she stayed in the thick of things with their 2 surviving children (another 2 died young) and smuggled gold worth £800 from the merchant, Sir Paul Pindar to the King. The marital estate at Horton was seized and occupied by Sir Thomas Fairfax for Parliament in 1646 and Cromwell’s daughter, Bridget, married Henry Ireton there. Fox includes a chapter on this even though Whorwood is nowhere to be seen. By 1647 Whorwood had a lover in the form of Sir Thomas Bendish; they were part of the King’s Newcastle entourage and she was smuggling letters and information to Charles.

The war opened up opportunities for political agency and physical adventure for women like Whorwood and she was not alone in her activities. Ann Fanshawe, for example, smuggled a packet of letters to Charles and Anne Halkett was in a similar mould to Whorwood, even taking on a lover in that context of political turmoil and war. Henrietta Maria was, of course, engaged in the same activities and the most influential of them all. These are the women who are not portrayed as war heroines in the histories. The heroines are those who fit the gender stereotype of the chaste woman defending the family at home (Brilliana Harley springs instantly to mind). The stereotypes are not useful and diminish female agency. Whorwood was liberated by war. Even when her husband returned home in 1647, she remained in the king’s circle and Brome seems to have accepted what Fox coyly calls her ‘working relationship’ with Bendish. Signing herself 409 in her letters, she acted as a conduit for Scottish invasion plans in spring 1648 and by summer she was collaborating with Henry Firebrace, who was custodian of the king, and exchanging letters with Charles almost daily. ‘You may freely trust Whorwood in anything that concerns my service’ Charles I told William Hopkins in 1648. He was right: she was integral to multiple escape plots in the spring and summer of 1648, though they all failed because Charles I proved supremely incompetent at doing things like squeezing out of windows.

On 24 July 1648 Charles found a way to smuggle Whorwood herself into his chamber where he ‘shall have 3 howres to embrace and nippe you’. This piece of juicy historical gossip about Charles I had already been revealed by Sarah Poynting in an article that destroys Charles’ reputation as that most uxorious of English male monarchs [‘Deciphering the King: Charles I’s Letters to Jane Whorwood’, The Seventeenth Century, 21:1 (2006), 128-40]. Poynting’s meticulous work on the royalist cipher has led to re-interpretation of Charles as ‘a complex man’ who, like many prisoners, occupied his days of incarceration thinking about ‘self-justification, escape and sex…[though] not always in that order’. She has decoded a letter from Charles to Whorwood (26/7/48) to read as follows: ‘there is one possible way you may get a swyving [fucking] from me’. Fox has reprinted this letter but consigned the full extent of the obscenity/proof of adultery to a footnote.

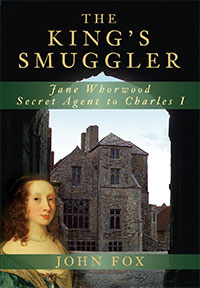

The picture on the dust cover of this book is of Carisbrooke Castle gatehouse, where much of the action (including sexual) took place. It is overlaid with an image of Jane Whorwood’s half-sister (‘with reddish hair but no pock marks’ notes the author). It seems a fitting visual metaphor for a book in which the subject is only half-present. The book is largely well-written, though given to sections of purple prose, and rather laboured similes and metaphors: I developed a particular liking for ‘her mother’s two marriages and her own wrapped her in family surnames like a fog’. At times the prose is so inventive that it is hard to know who or what is being talked about and in places tangential information has been squeezed into the narrative for no apparent reason. As far as I can tell, the ‘melancholic lone wolf of thirty-six’ crossing Wheatley Bridge on page 62 is the poet and radical politician, John Milton. I never worked out why I needed to hear about him or what he had to do with Jane Whorwood.

The King’s Smuggler did not radically alter my vision of Charles I or the role of some royalist women during the civil wars. John Fox’s assessment that ‘finding Jane Whorwood breaks new soil’ is a claim too far and much of the detail has been covered already by Poynting. However, Fox is right that Whorwood’s significance has been overlooked. Her contemporaries failed properly to measure the threat that she posed to reconciliation between Charles I and his parliament. Rather like Henrietta Maria, she colluded with Charles in his belief that he could just go on eluding his parliamentary (and New Model Army) enemies. In 1651 several people testified to the prominence of Whorwood in the several escape attempts made by Charles I, but she was only fined £600. Her sex saved her from the harsher punishment that would have come from being taken more seriously. In the few letters that survive, there she is, in code, as ‘715’ and ‘390’ and sometimes ‘N’ and sometimes ‘Hellen’. She was a spy. This book delivers a ripping yarn. I have not laughed so much in ages and cannot get the vision of Whorwood’s trysts with Charles I out of my head. It seems that in the case of Whorwood, the whore would. Readers: Enjoy!

Leave a Reply