Women’s History Walk around Radical Manchester

By Michael Herbert. Manchester was the world’s first great industrial city—‘Cottonopolis’—its privilege and poverty both dazzled and appalled by turn. It played a significant role in the formation of radical movements that challenged the status quo including trade unionism, co-operation, Chartism, socialism and feminism.

Table of Contents

- 1 The Co-operative Bank, Corporation Street.

- 2 City Buildings, Corporation Street, former offices of The Clarion newspaper

- 3 Cross Street, former site of the Manchester Guardian offices

- 4 Cross Street Chapel

- 5 Manchester Art Gallery, Mosley Street

- 6 Town Hall, Albert Square

- 7 Albert Square: The Manchester and Salford Women’s Trades and Labour Council

- 8 School Board Office

- 9 Former Free Trade Hall, Peter Street

- 10 Site of Peterloo Massacre, 1819

- 11 Site of the Hall of Science

- Need to Know…

1 The Co-operative Bank, Corporation Street.

The Co-operative movement came into being in the 1830s, inspired in part by manufacturer and social reformer Robert Owen. His statue stands outside the Bank. Two women’s movements arose from the Co-operative movement: the radical Owenite feminists of the 1830s—whom we shall meet later on—and the Co-operative Women’s Guild.

The Co-operative Women’s Guild was founded in April 1883 after a notice was placed in the ‘Women’s Corner’ of the Co-operative News by a Mrs Acland who wrote:

Men have had it all their own way in the News for a long time. It is a grand thing to have this corner all to ourselves, in which we women may open our minds to each other, and make known our thoughts and wants to each other, throughout the length and breadth of the land… What are women urged to do when Co-operative meetings are held? ‘Come and buy’ – that is all. We can be independent members of our Stores, but we are only asked to ‘come and buy’… Why should we not hold Co-operative mothers’ meetings, when we bring our work and sit together, one of us reading some Co-operative work aloud, which may afterwards be discussed?

By the time that the Co-operative Congress took place in Edinburgh in June, 50 women had already joined the League (as it was known initially) and its membership was growing rapidly. In July 1892 the women held a 3-day festival in Manchester to celebrate the formation of 100 branches of the Guild. One of the delegates wrote that for the women ‘this affair seemed to show them that they were of importance, and some of the older women marvelled at it’.

In 1911 the Guild gave evidence to the Royal Commission on Divorce Law Reform, the only organisation representing working-class women to do so. Four years later the Guild published Maternity: letters from working women, a collection of letters from members which described their own experiences of motherhood. The book disclosed the appalling plight of many working-class women who were dragged down by too many pregnancies and poor medical care.

…Cross Corporation Street to City Buildings immediately opposite the Bank

2 City Buildings, Corporation Street, former offices of The Clarion newspaper

The Socialist newspaper The Clarion was first published on 12 December 1891. Its offices were in City Buildings until 1895 when the paper moved to Fleet Street. The Clarion’s success was due mostly to its rumbustious mix of news, comment, short stories, songs and poetry. The paper included a ‘women’s column’ almost from the start. This was written initially by Eleanor Keeling and then, from October 1895, by Julia Dawson.

Julia Dawson

In February 1896 Julia informed her readers that she planned to organise a ‘Clarion van tour’ over the summer. A horse-drawn van had already been offered and this would head off, with 2 or 3 women on board, to stop in towns and villages to hold meetings and distribute socialist literature. Julia appealed for women to come forward as speakers as well as for donations to fund the venture. These appeals were successful and the ‘Clarion Van’ set off in June with 3 female speakers on board. It travelled from Liverpool to Cheshire and Staffordshire, and then went north, finishing its journey on Tyneside after 15 weeks’ hard campaigning. On the way the female speakers had addressed thousands of people and the initiative was judged a great success. The event was repeated for the next few years and by 1907 the number of ‘Clarion vans’ had risen to 6.

The Clarion’s supporters were divided in 1914 when proprietor Robert Blatchford supported the First World War at a time when many readers opposed it fervently. The paper survived until 1931 but was never the same.

…Walk along Corporation Street and then along Cross Street as far as Boots. This was the site of the Manchester Guardian’s offices, until they were demolished in the early 1970s

3 Cross Street, former site of the Manchester Guardian offices

The Manchester Guardian was founded in 1821 - but readers had to wait a century for the first women’s column which was introduced in 1922, edited by Madeline Linford. Linford recalled in 1963 that she had been the only woman on the staff and so had been instructed by the editor, C P Scott, to start a women’s feature on 6 days of the week:

…my briefing was lucid and firm. The page must be readable, varied and aimed always at the intelligent woman… I saw her as an aloof, rigid and highly critical figure, a kind of Big Sister, vigilant for lapses of taste, dignity and literary English.

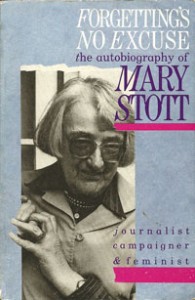

Linford recruited a talented set of contributors including Vera Brittain, Leonora Eyles, Winifred Holtby and Evelyn Sharp. Despite this, the column was axed in 1935 and did not re-appear until 1957 when Mary Stott was recruited to edit a new women’s page. Stott wrote later that she reckoned herself ‘a Guardian woman through and through’; certainly her Guardian women’s page became an institution in its own right and led directly to the birth of a number of women’s organisations. In February 1960, for instance, a letter was published from Maureen Nicol of Cheshire who wrote that ‘perhaps housebound housewives with liberal interests and desire to remain individuals could form a national register, so that whenever one moves one can contact like-minded friends’. When in response she received 400 letters in one week Nicol set up the National Housewive’s Register. Other organisations that the page acted as midwife to include the Pre-school Playgroups Association, Invalids at Home and The National Council for the Single Woman and her dependants.

Linford recruited a talented set of contributors including Vera Brittain, Leonora Eyles, Winifred Holtby and Evelyn Sharp. Despite this, the column was axed in 1935 and did not re-appear until 1957 when Mary Stott was recruited to edit a new women’s page. Stott wrote later that she reckoned herself ‘a Guardian woman through and through’; certainly her Guardian women’s page became an institution in its own right and led directly to the birth of a number of women’s organisations. In February 1960, for instance, a letter was published from Maureen Nicol of Cheshire who wrote that ‘perhaps housebound housewives with liberal interests and desire to remain individuals could form a national register, so that whenever one moves one can contact like-minded friends’. When in response she received 400 letters in one week Nicol set up the National Housewive’s Register. Other organisations that the page acted as midwife to include the Pre-school Playgroups Association, Invalids at Home and The National Council for the Single Woman and her dependants.

…Continue along Cross Street as far as the Unitarian Chapel at the bottom of Chapel Walks

4 Cross Street Chapel

In the 1830s the Unitarian Cross Street Chapel was a centre of reforming zeal. A minister there (for some 60 years) was William Gaskell, who married Elizabeth Stevenson (1810-1865) in 1832. After their honeymoon the couple set up home at 14 Dover Street in Manchester; in 1850 they moved to Plymouth Grove, to a house which is now being restored in Elizabeth Gaskell’s memory.

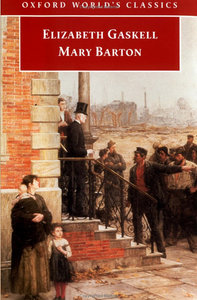

Manchester at Gaskell’s time was suffering from the aftermath of the depression of 1829, which had caused considerable industrial unrest, and from the 1832 cholera epidemic. Factories, dirty canals and slums surrounded the city centre. Witnessing the startling hardship of the poor at first hand, Gaskell began to distribute food and clothing, and to involve herself in charitable initiatives. Her first novel, Mary Barton, set in the industrial north, was published in 1848. Here some of the most distressing descriptions of the impoverished existence of local people echo the reports on poverty produced by the Manchester Domestic Mission which was based at Cross Street. Gaskell’s other novels include Cranford (1853), Ruth (1853), North and South (1854), Sylvia’s Lovers (1863) and Wives and Daughters (1865). Ruth attracted particular controversy for its narrative centering on an unmarried mother abandoned by her lover. According to Gaskell, some of her friends burned their copies after reading it. Gaskell had already touched on similar themes in ‘Lizzie Leigh’, a story about a Manchester prostitute, which had been published in Dickens’ periodical Household Words in March 1850.

Manchester at Gaskell’s time was suffering from the aftermath of the depression of 1829, which had caused considerable industrial unrest, and from the 1832 cholera epidemic. Factories, dirty canals and slums surrounded the city centre. Witnessing the startling hardship of the poor at first hand, Gaskell began to distribute food and clothing, and to involve herself in charitable initiatives. Her first novel, Mary Barton, set in the industrial north, was published in 1848. Here some of the most distressing descriptions of the impoverished existence of local people echo the reports on poverty produced by the Manchester Domestic Mission which was based at Cross Street. Gaskell’s other novels include Cranford (1853), Ruth (1853), North and South (1854), Sylvia’s Lovers (1863) and Wives and Daughters (1865). Ruth attracted particular controversy for its narrative centering on an unmarried mother abandoned by her lover. According to Gaskell, some of her friends burned their copies after reading it. Gaskell had already touched on similar themes in ‘Lizzie Leigh’, a story about a Manchester prostitute, which had been published in Dickens’ periodical Household Words in March 1850.

…Turn up King Street and then walk through to Mosley Street and enter the Manchester Art Gallery

5 Manchester Art Gallery, Mosley Street

The 19th-century art world was dominated by men, but a small number of women did succeed in working as artists. In 1876 the Manchester Society of Women Painters was founded by Annie Swynnerton (1844-1933) and Susan Isabel Dacre (1844-1933).

Annie Swynnerton was born in Salford and studied at the Manchester School of Art. Manchester Art Gallery is home to 18 of her paintings, including landscapes and portraits. She painted a portrait of William Gaskell in 1879, and also her fellow artist, Susan Isabel Dacre, in 1880.

Susan Isabel Dacre was born in Leamington and educated at a convent school in Salford. She worked as a governess in Paris and was in the city during the Franco–Prussian War and the Paris Commune. Returning to England, Dacre studied art at the Manchester School of Art where she met Annie Swynnerton. The 2 women become friends for life; they were both strong supporters of votes for women and Dacre was active in the Manchester Society for Women’s Suffrage whose driving force was Lydia Becker. Manchester Art Gallery has 16 works by Dacre, including a wonderful portrait of Lydia Becker.

In April 1913 a number of pictures in the Manchester Art Gallery were attacked by suffragettes Evelyn Manesta and Lillian Forrester, as part of the militant suffrage campaign. By this time Mrs Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union (the WSPU, founded in Manchester in 1903) was turning to more extreme militant tactics, including mass window-smashing, attacks on politicians and arson, out of frustration at Prime Minister Asquith’s dropping of the Suffrage Bill early in 1913.

In 2003 Home Office files revealed that in September 1913 the Home Office had ordered that photographs of suffragette prisoners be taken secretly. (This was done because so many of the women had refused to have their pictures taken.) These released files include a disturbing picture of Evelyn Manesta being held still by a prison warder. This image was used on a wanted poster of Manesta circulated by Scotland Yard - but it was doctored for publication to hide the warder’s arm around her throat.

…From the gallery, turn right into Princess Street and enter Albert Square

6 Town Hall, Albert Square

Manchester Council was established in 1838 after the reform of the borough system of local government. Women gained the right to vote in municipal elections in 1869, though it was many years before a woman was elected in Manchester. These are 3 of the early female councillors who have served the city:

Manchester Council was established in 1838 after the reform of the borough system of local government. Women gained the right to vote in municipal elections in 1869, though it was many years before a woman was elected in Manchester. These are 3 of the early female councillors who have served the city:

Margaret Ashton (1856-1937)

Margaret came from a wealthy mill-owning family who were strong supporters of the Liberal party. She was chair of the Lancashire and Cheshire Union of Women’s Liberal Associations and also active in the North of England Suffrage Society. In 1900 she was elected to Withington Urban District Council and in 1908 became the first woman to be elected onto Manchester City Council, representing Withington ward.

In September 1910 the first Women’s Municipal Lodging House in England was opened in Manchester, named in Margaret’s honour in recognition of her role in establishing the House. At the opening she said that she hoped the Lodging House would do something to lessen the crying shame of great cities - the fact that every night some women had nowhere to lay their head, because their scanty earnings were not enough to pay for a decent shelter.

Margaret opposed the First World War vehemently. She was a signatory of the ‘Open Christmas Letter’, a call for peace addressed ‘To the Women of Germany and Austria’ in January 1915, and a founder of the Manchester branch of the Women’s International League of Peace and Freedom. Margaret’s anti-war stance was condemned by the Council which in 1926 refused to hang a portrait of her commissioned by C P Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian, to mark her 70th birthday. The portrait was re-discovered by Alison Ronan whilst researching Manchester women’s history, and the portrait was unveiled in the Town Hall on 4 July 2006.

Ellen Wilkinson (1891-1947)

Ellen stood out for her views – and because she was less than 5ft tall. In 1902 she won a scholarship to attend Ardwick Higher Grade school which was later renamed the Ellen Wilkinson High School in her memory. In 1919 she gained a scholarship to read history at the University of Manchester - a considerable achievement for a young working-class woman at that time.

Ellen joined the Independent Labour Party at the age of 16 after hearing a speech by Katherine Glasier, one of the leading women socialists of the day:

It was a memorable meeting. I got a seat in the front row of the gallery. It seemed noisy to me, whose sole experience of meetings was of religious services. Rows of men filled the platform. But my eyes were riveted on a small slim woman her hair simply coiled into her neck, Katherine Glasier. She was speaking on ‘Socialism as a Religion’. To stand on a platform of the Free Trade Hall, to be able to sway a great crowd, to be able to make people work to make life better, to remove slums and underfeeding and misery just because one came and spoke to them about it - that seemed the highest destiny any woman could ever hope for.

At college Ellen was Secretary of the Fabian Society and the Socialist Federation and was also active in the Manchester Society for Women’s Suffrage. Like many ILP members, Ellen opposed the First World War and supported the ‘No Conscription Fellowship’; this opposed compulsory conscription and supported pacifists and conscientious objectors who refused to serve in the armed forces. In November 1923 she was elected as Labour councillor for the Gorton ward and, in 1924, as Labour MP for Middlesbrough East, one of the very few women in Parliament (at that time only women over 30 had the vote).

Ellen lost her seat in the catastrophic defeat of Labour in 1931, but returned to Parliament in 1935 as MP for Jarrow. In 1945 the new Labour Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, made her Minister of Education with the task of implementing the 1944 Education Act. In 1946 she was successful in steering the School Milk Act, which provided a free third pint of milk every day to every child in the country, through the Commons. She died suddenly on 6 February 1947 during one of the worst winters of the century. There is a plaque marking the site of her birth place (now demolished) in Baslam Close, Beswick.

Hannah Mitchell (1872 -1936)

Derbyshire-born Hannah was employed as a seamstress in Bolton when she began reading The Clarion newspaper and attending socialist meetings. Hannah gave her first public speech when The Clarion van came to Bolton; gaining confidence, she then began to speak at outdoor public meetings and at the local Labour church. To her surprise, she was soon in demand as a speaker.

In May 1904 Hannah was elected as a Poor Law Guardian in Ashton-under-lyne. Around this time she also joined Mrs Pankhurst’s WSPU. She visited the Pankhurst home in Nelson Street, Manchester, and spoke at many meetings around Lancashire. During the general election campaign she was arrested after interrupting a meeting addressed by Winston Churchill in St John’s School, Deansgate, and another addressed by Lloyd George at Hale. In the summer of 1906 Hannah was arrested again after interrupting a Liberal party meeting at Belle Vue. She was sent to prison but was released early—much to her annoyance—after her husband paid her fine. During the campaign to elect the socialist Victor Grayson as MP for Colne Valley, Hannah collapsed with exhaustion and suffered a nervous breakdown. It took her a long time to recover.

In 1924 Hannah was elected to Manchester City Council for the Labour party and remained a member until 1935. She was especially proud of her work on the Baths Committee which established public wash houses in working class areas – ’…a real public service greatly appreciated by women.’ After leaving the Council Hannah served as a magistrate. She had been working on her autobiography for many years; after her death it was found amongst her papers and published in 1968 under the title The Hard Way. It is now considered a classic account of a working-class woman’s personal and political emancipation.

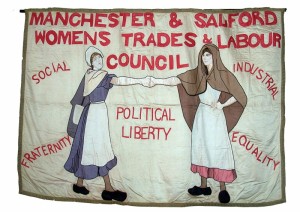

7 Albert Square: The Manchester and Salford Women’s Trades and Labour Council

Image courtesy of the Working Class Movement Library

The Manchester and Salford Women’s Trades Council was created at a meeting in the Town Hall in 1895 to encourage women’s participation in trade unions. The Council had 2 paid organisers: Sarah Dickenson and Frances Ashwell. When Frances left to get married, her replacement was Eva Gore-Booth, who took up the post in June 1900. The Council’s office was at 9 Albert Square.

Eva was born in Sligo to a prominent Anglo-Irish family. The turning point in her life came in 1896 when she met Esther Roper who told her about her work in Manchester for trade union organisation amongst women and for women’s right to vote. Eva decided to leave Ireland and move to Manchester to help Esther in her work, sharing a house with her in Rusholme and later in Victoria Park.

Sarah and Eva were firmly of the opinion that they should campaign for women’s trade unionism and suffrage, and resigned their posts in 1904 when a motion in favour of suffrage was rejected at a meeting of the Council’s committee. (This tension between socialism and women’s rights was a common aspect of the wider working-class movement at this time.) In September the 2 women set up a new body—the Manchester and Salford Women’s Trades and Labour Council—which shared offices at 5 John Dalton Street. Their banner survives and can be seen on display in the Working Class Movement Library (the 2 Trades Councils were finally re-united in 1919).

Esther recalled years ‘full to overflowing with organisation… On different occasions, women pit-brow workers, barmaids, women acrobats and gymnasts, and women florists were successfully organised in their own defence.’ Eva also found time to write poetry and plays, and to teach drama to young women in the University Settlement at Ancoats Hall. When the war broke out in 1914 Eva and Ether opposed it as pacifists. In 1915 they joined the Women’s Peace Crusade and travelled the country speaking in support of a negotiated peace to end the war.

Eva died at her home, which was now in Southern England, on 30 June 1926 and was buried at St John’s Church, Hampstead. Esther died in April 1938 and was buried in the same grave as Eva.

…Leave Albert Square and go down Jacksons Row to the former School Board Office situated at the junction with Deansgate, now a temporary library whilst Central Library is closed

8 School Board Office

Lydia Becker, c 1873

Lydia Becker (1827-1890) was Secretary of the Manchester National Society for Women’s Suffrage from 1867 until her death in 1890. She encouraged women to campaign and speak publicly, and laid the basis for the successful campaign of the early 20th century.

In the autumn of 1866 Lydia joined the recently-formed Manchester Committee which was collecting signatures for a petition on women’s suffrage. She also put pen to paper and in March 1867 an article by her on the subject was published in the Contemporary Review:

It surely will not be denied that women have, and ought to have opinions of their own on subjects of public interest, and on the events which arise as the world wends on its way. But if it be granted that women may, without offence, hold political opinions, on what ground can the right be withheld of giving the same expression or effect to their opinions as that enjoyed by their male neighbours?

Lydia realised that the Cause was not going to be won easily. On 14 April 1868 she organised a public meeting in the assembly rooms of the Free Trade Hall, a meeting often celebrated as marking the beginning of the suffrage campaign. Very unusually for that time women were on the platform and spoke. In the spring of 1869 Lydia undertook a series of lectures in the north of England. She gained more confidence in public speaking and in dealing with the male hecklers who were invariably present. Never physically strong, she was often exhausted by these trips.

Despite dogged rejection by the Commons of women’s right to vote for MPs, in 1869 women were granted the right to vote in municipal elections with surprisingly little controversy. The Manchester Society sent circulars to women voters explaining their right to vote and how to vote (until Gladstone’s 1872 Ballot Act this was still done in public and could be daunting).

The following year women also gained the right to vote, and stand for election to, the new School Boards. Lydia stood successfully for the Manchester School Board as an independent member, receiving 15,000 votes, and remained a member until her death. As her suffrage activities, Lydia’s education work gave her a high public profile as she gave speeches and attended the opening of new Board Schools. Laying the foundation stone of a new school in Burgess Street she said:

It was a great mistake to suppose that domestic duties were limited to girls and women, every boy in Manchester should be taught to darn his own socks and cook his own chops.

In 1870 Lydia and other women founded the monthly Women’s Suffrage Journal which chronicled the progress and frustrations of the national campaign for women’s suffrage. When she died suddenly in Switzerland in July 1890 (where she had gone to recuperate) the Women’s Suffrage Journal ceased publication, unable to fill the void that she left.

…Go back up Jacksons Row and then walk around the corner to Peter Street to the Radisson Hotel , formerly the Free Trade Hall, Manchester’s premier meeting hall

9 Former Free Trade Hall, Peter Street

Christabel Pankhurst, courtesy of University of Texas Libraries at Austin

On 10 October 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst called a meeting in her house of her women comrades in the Independent Labour Party (ILP). By the end of the evening they had agreed to set up a new organisation: the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Initially the women lobbied to get motions passed at ILP branches urging the leadership to take action on women’s suffrage. They managed to get a Private Members Bill before the Commons, sponsored by the Liberal MP John Bamford Slack, on 12 May 1905. Women packed the lobby of the Commons expectantly in support of the bill, but it was talked out.

With a general election in the offing which many expected the Liberals to win, Sir Edward Grey, a leading member of the Liberal party, came to speak in Manchester on 13 October 1905 at the Free Trade Hall. The WSPU wrote to him, asking him to receive a deputation, but he did not reply. Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney joined the audience. This is Sylvia Pankhurst’s account of what occurred:

Sir Edward Grey was making his appeal for the return of a Liberal government when a little white ‘Votes for Women’ banner shot up. ‘Labour Representation’ was the cry of the hour. Christabel thrust Annie Kenney forward, as one of the organised textile workers, and a member of a trade union committee, to ask ‘will the Liberal Government give women the vote?’ Other questions were answered; that question was ignored. When it was persisted in, Annie Kenney was dragged down by the men sitting near her, and one of the stewards put a hat over her face. Christabel repeated the question. The hall was filled with conflicting cries; ‘Be quiet’, ‘Let the lady speak’. In the midst of the hubbub the Chief Constable of Manchester, William Peacock, came to the women and told them that if they would put the question in writing, he would take it himself to Sir Edward Grey; but it went the round of chairman and speakers, and none of them vouchsafed a reply. When Sir Edward Grey rose to acknowledge a vote of thanks, Annie stood on a chair to ask again, whilst Christabel strove to prevent her removal; but Liberal stewards and policemen in plain clothes soon dragged them both from the hall.

Annie Kenney Image: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress)

They were arrested and appeared in court the following day. They refused to pay their fines and hence Christabel was sentenced to 7 days imprisonment and Annie to 3 days. On their release a great crowd greeted them and Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper presented them with flowers. On 20 October both women addressed a crowded meeting in the very hall from which they had been ejected a week earlier. It was the beginning of the militant campaign for women’s suffrage.

…From the Free Trade Hall walk around the corner to the space in front of GMEX, formerly Manchester Central station, now an exhibition hall

10 Site of Peterloo Massacre, 1819

Detail from Massacre at St Peters (Manchester, England) by George Cruikshank (1819)

The Peterloo massacre took place here on 16 August 1819. A crowd of tens of thousands of working men and women, and some children, had gathered in a field on the edge of town to demand political reform when they were attacked without warning by yeomanry on horses and soldiers armed with swords. The crowd was dispersed brutally in just a few bloody minutes. It was one of the most traumatic political events in Manchester’s history. At least 18 people were killed, 4 of whom were women; over 650 people were recorded as injured, 168 of whom were women.

The movement for political reform had been in existence in one form or another since the 1790s, inspired by the American and French Revolutions and the writings of Thomas Paine. It had been driven underground by government repression during the wars against France but re-emerged after 1815. The movement attracted a new energetic audience amongst the working people of the industrial towns of the north and included women who organised Female Reform Societies. The women called for reform and votes for men but did not at this stage demand rights for themselves.

On 10 July the radical Manchester Observer had printed an address from the Blackburn Society which called on every man in England to join reform societies and fight for annual parliaments, universal suffrage and election by ballot ‘which alone can save us from lingering misery and premature death’. The address also referred to the importance that women attached to their position as mothers and to educating their children in democratic ideas.

The Manchester Female Reform Society was also formed in July 1819 and issued its own address, entitled Dear Sisters of the Earth. It was an appeal directed ‘to the wives, mothers, sisters and daughters of the higher and middling classes of society’:

It is with a spirit of peaceful consideration and due respect that we are induced to address you, upon the causes that have compelled us to associate together in aid of our suffering children, our dying parents, and the miserable partners of our woes… Our minds are filled with a horror and despair, fearful on each returning morn, the light of heaven should present to us the corpse of some of our famished offspring, or nearest kindred, which the more kind hand of death had released from the oppressor…

The vivid description of the attack on the crowd and its aftermath by Samuel Bamford, published in his book Passages in the Life of a Radical (1844), is well-known and almost invariably quoted in any account of Peterloo. Less well-known is the equally vivid account by his wife Jemima Bamford in the same book:

The meeting was all in a tumult; there were dreadful cries; the soldiers kept riding amongst the people, and striking with their swords. I became faint, and turning from the door, I went unobserved down some steps into a cellared passage; and hoping to escape from the horrid noise, and to be concealed, I crept into a vault, and sat down, faint and terrified, on some fire wood. The cries of the multitude outside, still continued, and the people of the house, up stairs, kept bewailing most pitifully. They could see all the dreadful work through the window, and their exclamations were so distressing, that I put my fingers in my ears to prevent my hearing more; and on removing them, I understood that a young man had just been brought past, wounded. The front door of the passage before mentioned, soon after opened, and a number of men entered, carrying the body of a decent, middle aged woman, who had been killed. I thought they were going to put her beside me, and was about to scream, but they took her forward, and deposited her in some premises at the back of the house.

Some of the crowd fought back. Samuel Bamford recorded the following anonymous fighter:

A heroine, a young married woman of our party, with her face all bloody, her hair streaming about her, her bonnet hanging by the string, and her apron weighed with stones, kept her assailant at bay until she fell backwards and was near being taken; but she got away covered with severe bruises.

…Walk down Deansgate and turn right down Tonman Street to the corner with Byrom Street which is where the Hall of Science once stood

11 Site of the Hall of Science

In 1835 Salford Co-operators built and opened a Co-operative Social Institute on Great George Street which could hold up to 600 people. Within a few years the Owenites had outgrown the Institute and in January 1840 they moved to a purpose-built new home, the Hall of Science on Byrom Street, which was opened by Robert Owen. The hall bore the motto ‘Sacred to the Investigation of Truth’. Some of the Owenites now called themselves socialists, using the word for the first time. There were evening and Sunday lectures held here, concerts, parties, excursions, and a Sunday school which by 1842 had 250 pupils. Women lecturers included Anna Wheeler, Emma Martin, Eliza Macauley, Margaret Chappelsmith - and Frances Morrison who advocated a revolution in relations between men and women and a new, equal form of marriage.

Frances was born in Surrey, the illegitimate daughter of a farm labourer. Aged just 16 she ran off with James Morrison, a house-painter who was tramping the country looking for work. They lived together until she became pregnant when they got married. The couple had many children and lived in Birmingham where Frances ran a newspaper shop and began reading Robert Owen’s work. She later wrote to him ‘Long ‘ere I began to think, my reason warred with the absurd forms of society, but from an ill-cultivated and wrong direction given to my mind, I could never get a solid idea until the perusal of your Essays’.

After her husband’s death in 1835, Frances became a paid Owenite lecturer, speaking across the north. She moved to Salford in the late 1830s. In July 1839 she spoke at a meeting on New George Street, Shudehill and the following report appeared in the New Moral World:

…the place was crowded to suffocation. She commenced her lecture with astonishing firmness and composure ….The subject of her lecture was confined principally to the feeling and principal that should guide or actuate these who call themselves Socialist. Her manner was peculiarly energetic, her arguments well-arranged, and her remarks judiciously adapted to the occasion, and characterised by remarkable simplicity and delicacy. She was listened to with respectful attention and seemed to give general satisfaction. She is the first female in Manchester who has had the nerve to come forward in practical advocacy of our views, and it is hoped that her example will operate as stimulus to others to lend their exertions in promoting the great cause of socialism, whose interests are so completely identified with their own.

Frances became a teacher in Hulme with the help of Robert Owen and seems to have given up lecturing. She enjoyed a long life and died in 1898. The Hall of Science only survived until 1850 when, after splits and divisions within the Owenite movement, it was sold and the Manchester Free Library was housed in the building. In 1877 the Hall was demolished after its structure had become weakened by the weight of books.

This is the end of the walk. From here it is a short distance to Deansgate railway station or GMEX metro stop.You can also board the No 2 bus (which is free) which runs along Deansgate to Victoria railway station in one direction or to Oxford Road railway station in the other directiom. Full information on transport is available from GMPTE: www.gmpte.com

Need to Know…

Michael Herbert has been researching and writing about Manchester’s radical working-class history for many years. He is a Trustee of the Working Class Movement Library and has edited the North West Labour History Journal. His published work includes The Wearing of the Green: A Political History of the Irish in Manchester (2000).

Leave a Reply